Major extinction events

Although the Cretaceous-Tertiary (or K-T)

extinction event is the most well-known because it wiped out the dinosaurs, a

series of other mass extinction events has occurred throughout the history of

the Earth, some even more devastating than K-T. Mass extinctions are periods in

Earth's history when abnormally large numbers of species die out simultaneously

or within a limited time frame. The most severe occurred at the end of the

Permian period when 96% of all species perished. This along with K-T are two of

the Big Five mass extinctions, each of which wiped out at least half of all

species. Many smaller scale mass extinctions have occurred, indeed the

disappearance of many animals and plants at the hands of man in prehistoric,

historic and modern times will eventually show up in the fossil record as mass

extinctions.

Ordovician-Silurian mass extinction

The third largest extinction in Earth's

history, the Ordovician-Silurian mass extinction had two peak dying times

separated by hundreds of thousands of years. During the Ordovician, most life

was in the sea, so it was sea creatures such as trilobites, brachiopods and

graptolites that were drastically reduced in number.

Late Devonian mass extinction

Three quarters of all species on Earth died

out in the Late Devonian mass extinction, though it may have been a series of

extinctions over several million years, rather than a single event. Life in the

shallow seas were the worst affected, and reefs took a hammering, not returning

to their former glory until new types of coral evolved over 100 million years

later.

Permian mass extinction

The Permian mass extinction has been

nicknamed The Great Dying, since a staggering 96% of species died out. All life

on Earth today is descended from the 4% of species that survived.

Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction

During the final 18 million years of the

Triassic period, there were two or three phases of extinction whose combined

effects created the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction event. Climate change,

flood basalt eruptions and an asteroid impact have all been blamed for this

loss of life.

Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction

The Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction -

also known as the K/T extinction - is famed for the death of the dinosaurs.

However, many other organisms perished at the end of the Cretaceous including

the ammonites, many flowering plants and the last of the pterosaurs.

Importance of mass Extinction events in Evolution

Mass extinctions have sometimes accelerated

the evolution of life on Earth. When dominance of particular ecological niches

passes from one group of organisms to another, it is rarely because the new

dominant group is "superior" to the old and usually because an

extinction event eliminates the old dominant group and makes way for the new

one.

For example mammaliformes ("almost

mammals") and then mammals existed throughout the reign of the dinosaurs,

but could not compete for the large terrestrial vertebrate niches which

dinosaurs monopolized. The end-Cretaceous mass extinction removed the non-avian

dinosaurs and made it possible for mammals to expand into the large terrestrial

vertebrate niches. Ironically, the dinosaurs themselves had been beneficiaries

of a previous mass extinction, the end-Triassic, which eliminated most of their

chief rivals, the crurotarsans.

Causes of particular mass extinctions

Flood

basalt events: Eleven occurrences, all associated

with significant extinctions. Only five of the major extinctions coincided with

flood basalt eruptions and that the main phase of extinctions started before

the eruptions.

Basaltic eruptions can have series of

interrelated effects. A basaltic eruption could have

1.

produced dust and particulate

aerosols which inhibited photosynthesis and thus caused food chains to collapse

both on land and at sea

2.

emitted sulfur oxides which

were precipitated as acid rain and poisoned many organisms, contributing further

to the collapse of food chains

3.

emitted carbon dioxide and thus

possibly causing sustained global warming once the dust and particulate

aerosols dissipated.

Flood basalt events occur as pulses of

activity punctuated by dormant periods. As a result they are likely to cause

the climate to oscillate between cooling and warming, but with an overall trend

towards warming as the carbon dioxide they emit can stay in the atmosphere for

hundreds of years.

It is speculated that massive volcanism

caused or contributed to the End-Permian, End-Triassic and End-Cretaceous

extinctions.

2. Sea-level falls

Sea-level falls could reduce the

continental shelf area (the most productive part of the oceans) sufficiently to

cause a marine mass extinction, and could disrupt weather patterns enough to

cause extinctions on land. But sea-level falls are very probably the result of

other events, such as sustained global cooling or the sinking of the mid-ocean

ridges.Sea-level falls are associated with most of the mass extinctions,

including all of the "Big Five"—End-Ordovician, Late Devonian,

End-Permian, End-Triassic, and End-Cretaceous.

3. Impact events

The impact of a sufficiently large asteroid

or comet could have caused food chains to collapse both on land and at sea by

producing dust and particulate aerosols and thus inhibiting photosynthesis.

Impacts on sulfur-rich rocks could have emitted sulfur oxides precipitating as

poisonous acid rain, contributing further to the collapse of food chains. Such

impacts could also have caused megatsunamis and/or global forest fires.

The Shiva hypothesis proposes that periodic

gravitational disturbances cause comets from the Oort cloud to bombard earth

every 26 to 30 million years.

4. Ocean asteroid impact

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) is soluble in sea

water and is present in very large quantities. It mostly reports as the

bicarbonate radical (−HCO3) which is only stable at temperatures below 50°C.Sea

surface temperatures are normally below 50°C, but can easily exceed that

temperature when an asteroid strikes the ocean thereby inducing a large thermal

shock. Under those circumstances very large quantities of CO2 erupt from the

ocean. As a heavy gas, the CO2 can quickly spread around the world in

concentrations sufficient to suffocate air breathing fauna, selectively at low

altitudes.Asteroid impacts with the ocean may not leave obvious signs, but

these impacts have the potential to be far more devastating to life on earth

than impacts with land.

5. Sustained and significant global cooling

Sustained global cooling could

·

kill many polar and temperate species and force others to migrate

towards the equator;

·

reduce the area available for

tropical species;

·

often make the Earth's climate

more arid on average, mainly by locking up more of the planet's water in ice

and snow.

The glaciation cycles of the current ice

age are believed to have had only a very mild impact on biodiversity, so the

mere existence of a significant cooling is not sufficient on its own to explain

a mass extinction.

It has been suggested that global cooling

caused or contributed to the End-Ordovician, Permian-Triassic, Late Devonian

extinctions, and possibly others. Sustained global cooling is distinguished

from the temporary climatic effects of flood basalt events or impacts.

6.Sustained and significant global warming

This would have the opposite effects:

·

expand the area available for

tropical species;

·

kill temperate species or force

them to migrate towards the poles;

·

possibly cause severe

extinctions of polar species;

·

often make the Earth's climate

wetter on average, mainly by melting ice and snow and thus increasing the

volume of the water cycle.

It might also cause anoxic events in the

oceans.

Global warming

as a cause of mass extinction is supported by several recent studies.The most

dramatic example of sustained warming is the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum,

which was associated with one of the smaller mass extinctions. It has also been

suggested to cause the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, during which 20% of

all marine families went extinct. Furthermore, the Permian–Triassic extinction

event has been suggested to have been caused by warming. Human-caused global

warming is contributing to extinctions today.

7.Clathrate gun methane eruptions

Clathrates are composites in which a

lattice of one substance forms a cage around another. Methane clathrates (in

which water molecules are the cage) form on continental shelves. These

clathrates are likely to break up rapidly and release the methane if the

temperature rises quickly or the pressure on them drops quickly—for example in

response to sudden global warming or a sudden drop in sea level or even

earthquakes. Methane is a much more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon

dioxide, so a methane eruption ("clathrate gun") could cause rapid

global warming or make it much more severe if the eruption was itself caused by

global warming.

It has been suggested that "clathrate

gun" methane eruptions were involved in the end-Permian extinction and in

the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, which was associated with one of the

smaller mass extinctions.

8. Anoxic events

Anoxic events are situations in which the

middle and even the upper layers of the ocean become deficient or totally

lacking in oxygen. Their causes are complex and controversial, but all known

instances are associated with severe and sustained global warming, mostly

caused by sustained massive volcanism.

It has been suggested that anoxic events

caused or contributed to the Ordovician–Silurian, late Devonian,

Permian–Triassic and Triassic–Jurassic extinctions, as well as a number of

lesser extinctions. On the other hand, there are widespread black shale beds

from the mid-Cretaceous, which indicate anoxic events but are not associated

with mass extinctions.

9. Hydrogen sulfide emissions from the seas

During the Permian–Triassic extinction

event the warming also upset the oceanic balance between photosynthesising

plankton and deep-water sulphate-reducing bacteria, causing massive emissions

of hydrogen sulphide which poisoned life on both land and sea and severely

weakened the ozone layer, exposing much of the life that still remained to

fatal levels of UV radiation.

10. Oceanic overturn

Oceanic overturn is a disruption of thermohaline

circulation which lets surface water (which is more saline than deep water

because of evaporation) sink straight down, bringing anoxic deep water to the

surface and therefore killing most of the oxygen-breathing organisms which

inhabit the surface and middle depths. It may occur either at the beginning or

the end of a glaciation, although an overturn at the start of a glaciation is

more dangerous because the preceding warm period will have created a larger

volume of anoxic water

It has been suggested that oceanic overturn

caused or contributed to the late Devonian and Permian–Triassic extinctions.

11. A nearby nova, supernova or gamma ray burst

A nearby gamma ray burst at the

End-Ordovician extinction would be powerful enough to destroy the Earth's ozone

layer, leaving organisms vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

Gamma ray bursts are fairly rare, occurring only a few times in a given galaxy

per million years.

12. Geomagnetic reversal

Increased geomagnetic reversals will weaken

Earth's magnetic field destroy magnetosphere, long enough to expose the

atmosphere to the solar winds, causing oxygen ions to escape the atmosphere,

resulting in a disastrous drop on oxygen. Additionally, Magnetosphere

destruction will cause the earth to be bombarded with Alpha, beta, gamma and X rays,

wiping out lives.

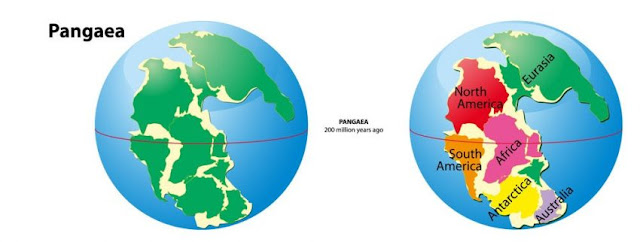

13. Plate tectonics

Movement of the continents into some

configurations can cause or contribute to extinctions in several ways:

·

by initiating or ending ice

ages;

·

by changing ocean and wind

currents and thus altering climate;

·

by opening seaways or land

bridges which expose previously isolated species to competition for which they

are poorly adapted (for example, the extinction of most of South America's

native ungulates and all of its large metatherians after the creation of a land

bridge between North and South America).

Occasionally plate tectonics creates a super-continent

which includes the vast majority of Earth's land area, which is likely to

reduce the total area of continental shelf (the most species-rich part of the

ocean) and produce a vast, arid continental interior which may have extreme

seasonal variations.