The Permian Period was the final period of the Paleozoic Era. Lasting

from 299 million to 251 million years ago, it followed the Carboniferous Period

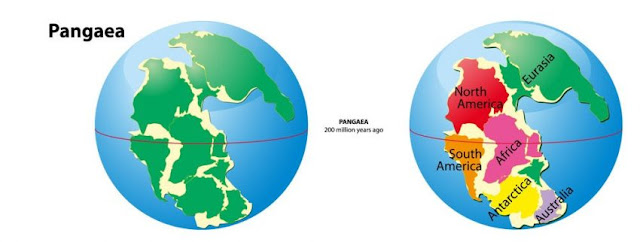

and preceded the Triassic Period. By the early Permian, the two great

continents of the Paleozoic, Gondwana and Euramerica, had collided to form the

supercontinent Pangaea. Pangaea was shaped like a thickened letter “C.” The top

curve of the “C” consisted of landmasses that would later become modern Europe

and Asia. North and South America formed the curved back of the “C” with Africa

inside the curve. India, Australia and Antarctica made up the low curve. Inside

the “C” was the Tethys Ocean, and most of the rest of Earth was the

Panthalassic Ocean. Because Pangaea was so immense, the interior portions of

the continent had a much cooler, drier climate than had existed in the

Carboniferous.

Marine life

Little is known about the huge Panthalassic Ocean, as there is little

exposed fossil evidence available. Fossils of the shallower coastal waters

around the Pangaea continental shelf indicate that reefs were large and diverse

ecosystems with numerous sponge and coral species. Ammonites, similar to the

modern nautilus, were common, as were brachiopods. The lobe-finned and spiny

fishes that gave rise to the amphibians of the Carboniferous were being

replaced by true bony fish. Sharks and rays continued in abundance.

Plants

On land, the giant swamp forests of the Carboniferous began to dry out.

The mossy plants that depended on spores for reproduction were being replaced

by the first seed-bearing plants, the gymnosperms. Gymnosperms are vascular

plants, able to transport water internally. Gymnosperms have exposed seeds that

develop on the scales of cones and are fertilized when pollen sifts down and

lands directly on the seed. Today’s conifers are gymnosperms, as are the short

palm like cycads and the gingko.

Insects

Arthropods continued to diversify during the Permian Period to fill the

niches opened up by the more variable climate. True bugs, with mouthparts

modified for piercing and sucking plant materials, evolved during the Permian.

Other new groups included the cicadas and beetles.

Land animals

Two important groups of animals dominated the Permian landscape:

Synapsids and Sauropsids. Synapsids had skulls with a single temporal opening

and are thought to be the lineage that eventually led to mammals. Sauropsids

had two skull openings and were the ancestors of the reptiles, including

dinosaurs and birds.

In the early Permian, it appeared that the Synapsids were to be the

dominant group of land animals. The group was highly diversified. The earliest,

most primitive Synapsids were the Pelycosaurs, which included an apex predator,

a genus known as Dimetrodon. This animal had a lizard-like body and

a large bony “sail” fin on its back that was probably used for

thermoregulation. Despite its lizard-like appearance, recent discoveries have

concluded that Dimetrodon skulls, jaws and teeth are closer to

mammal skulls than to reptiles. Another genus of Synapsids, Lystrosaurus, was

a small herbivore — about 3 feet long (almost 1 meter) — that looked something

like a cross between a lizard and a hippopotamus. It had a flat face with two

tusks and the typical reptilian stance with legs angled away from the body.

In the late Permian, Pelycosaurs were succeeded by a new lineage known

as Therapsids. These animals were much closer to mammals. Their legs were under

their bodies, giving them the more upright stance typical of quadruped mammals.

They had more powerful jaws and more tooth differentiation. Fossil skulls show

evidence of whiskers, which indicates that some species had fur and were

endothermic. The Cynodont (“dog-toothed”) group included species that hunted in

organized packs. Cynodonts are considered to be the ancestors of all modern

mammals.

At the end of the Permian, the largest Synapsids became extinct, leaving

many ecological niches open. The second group of land animals, the Sauropsid

group, weathered the Permian Extinction more successfully and rapidly

diversified to fill them. The Sauropsid lineage gave rise to the dinosaurs that

would dominate the Mesozoic Era.

The Great Dying

The Permian Period ended with the greatest mass extinction event in

Earth’s history. In a blink of Geologic Time — in as little as 100,000 years —

the majority of living species on the planet were wiped out of existence.

Scientists estimate that more than 95 percent of marine species became extinct

and more than 70 percent of land animals. Fossil beds in the Italian Alps show

that plants were hit just as hard as animal species. Fossils from the late

Permian show that huge conifer forests blanketed the region. These strata are

followed by early Triassic fossils that show few signs of plants being present

but instead are filled with fossil remnants of fungi that probably proliferated

on a glut of decaying trees.

Scientists are unclear about what caused the mass extinction. Some point

to evidence of catastrophic volcanic activity in Siberia and China (areas in

the northern part of the “C” shaped Pangaea). This series of massive eruptions

would have initially caused a rapid cooling of global temperatures leading to

increased glaciations. This “nuclear winter” would have led to the demise of

photosynthetic organisms, the basis of most food chains. Lowered sea levels and

volcanic fallout would account for the evidence of much higher levels of carbon

dioxide in the oceans, which may have led to the collapse of marine ecosystems.

Other scientists point to indications of a massive asteroid impacting the

southernmost tip of the “C” in what is now Australia. Whatever the cause, the

Great Dying closed the Paleozoic Era.

No comments:

Post a Comment